|

■

Home ■ site map |

|

Saturated fats and unsaturated fats

Dietary fats

- Cholesterol -

Saturated/unsaturated -

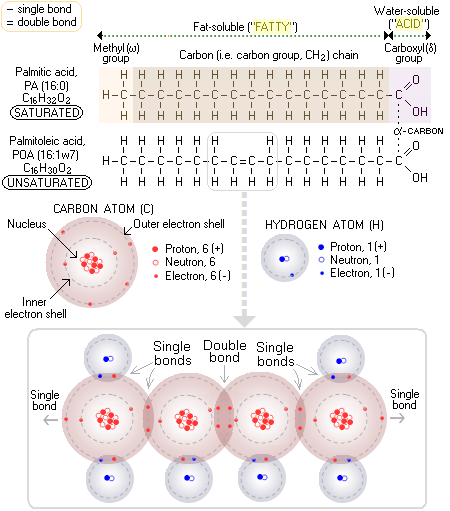

Hydrogenated Another type of dietary fat with not really deserved reputation of being a "bad fat" are saturated fats. These fats are needed by the body, and will become a health problem only when taken in excess - which is pretty much common to all nutrients. What is the difference between saturated and unsaturated fats? Well, dietary lipids come either in the form of fat (which is, by definition, solid on room temperature) or oil (liquid), depending on the nature of their building blocks - fatty acids. Fats are solid because they have higher melting point than oils; and they have higher melting point because they consist mainly from saturated fatty acids - stearic, palmitic, butyric and arachidic. Thus, the term "unsaturated fats" is formally incorrect, since these are, by definition, oils. The straight molecular form of saturated fatty acids makes it easy for them to align with each other; coupled with the absence of electrical charge, this makes saturated fatty acids tend to aggregate or, plainly put, makes them sticky. The attribute "saturated" comes from the property of molecular structure of a fatty acid where all carbon atoms have a single bond with each other. Since every carbon atom can have up to four bonds, this makes for a maximum possible number of bonds - that is, saturation - with hydrogen atoms (atomic bonds are particularly stable when two atoms share eight electrons in their outer electron shells; this made carbon atom, with 4 electrons in its outer shell, and low repulsive force of its two inner electrons and small nucleus, able to form strong carbon-to-carbon bonds - the basis of all organic molecules). For instance, palmitic acid (PA), one of the most common saturated fatty acids (the second major fatty acid in mother's milk), and the starting fatty acid (as its ionized form, palmitate) of fatty acid synthesis in your body, has fifteen carbon atoms in the "fatty" - i.e. fat soluble - portion of its molecule (methyl group and carbon chain) single-bonded to the maximum possible number of 31 atoms of hydrogen; hence, it is saturated. Since it has a total of 16 carbon atoms, and no double bonds between them, it is abbreviated 16:0. Taking two hydrogen atoms out of the carbon chain (by enzymatic action) of palmitic acid results in a double bond forming between two carbon atoms in the chain. While the number of carbon atoms in the chain - and the maximum number of their single bonds with hydrogen - remains unchanged (32), the actual number of bonded hydrogen atoms is now only 30, making this fatty acid - palmitoleic acid (POA), a minor constituent of olive oil - (mono)unsaturated. Since its only double bond forms between the 7th and 8th carbon atom, beginning from the first carbon atom in its methyl, or omega group, this fatty acid is abbreviated 16:1ω7 (so it can be called Omega-7 fatty acid). The major fatty acid in mother's milk - and in olive oil - oleic acid, is monounsaturated, containing 18 carbon atoms, with its only double bond between the 9th and 10th carbon atom from the omega end (hence abbreviated as 18:1ω9).

On the other hand, fatty acids with one or more double bonds between their carbon atoms have fewer than the maximum possible hydrogen bonds, which makes them (hydrogen) unsaturated. The presence of a double bond has two consequences with respect to their molecules: they are curled in shape, and have low negative electrical charge, which prevents them from aggregating together. More specifically, they don't aggregate when with a single double bond (monounsaturated), and if with two or three double bonds (polyunsaturated and super-unsaturated) they tend to disperse. Due to this property, unsaturated fatty acids act as anti-coagulants in the blood stream, unlike saturated fatty acids, which tend to make the blood sticky for hours after a fatty meal. The body uses saturated fatty acids mainly as a source of energy, but also as a building material (cell membranes). It obtains them either directly from food, or by conversion from sugars and starches. It is only when the level of saturated fatty acids in the body becomes excessive that they become a health problem. And this occurs when the rate of their absorption/conversion is higher than the rate at which the body burns the excess for energy. Obviously, the key is in balancing your saturated lipids and carbohydrate intake with your physical activity. Another common scenario of excess saturated fats intake being unhealthy over-consumption of animal fats from meats, eggs or dairy. Here, it is not saturated fats themselves, but the accompanying animal-made unsaturated fatty acid - arachidonic acid, also made by our own bodies - that does the harm. It is metabolized by the body to pro-inflammatory 2 Series prostaglandins and leukotrienes, more so when Omega-3 unsaturated fatty acid intake is low. These prostaglandins also make blood platelets more sticky, further promoting their aggregation and clot formation. While the excess of saturated fats, as with any other dietary component, is unhealthy, so can be their insufficient intake. Saturated fats are used by the body in regulating fluidity of cellular membranes, which must be in a very narrow range to allow for its optimum functioning. If they are unavailable in sufficient quantity, the membranes may become too fluid, prompting the body to produce more cholesterol in order to stiffen the membranes. This, under certain circumstances, could result in elevated cholesterol level which, in turn, under certain circumstances - such as lack of antioxidants - can threaten your health. As always, optimum health requires near-optimum balance of nutrients. Unsaturated fatty acids are entirely different story. Instead of sticking together, they tend to disperse, a property that supports cardiovascular health, and also allows them to be used for complex functions in cellular membranes. Those with a single double bond are called monounsaturated (e.g. oleic acid in milk, olives and most nuts), while those with two or more double bonds are polyunsaturated. The most important polyunsaturated fatty acid with two double bonds is linoleic acid (LA). Triple double bond in a fatty acid molecule brings us to super-unsaturated Omega-3 fatty acids, the three most important ones being alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), and gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) in borage, hemp and primrose oils. Arachidonic acid (AA) in animals has four double bonds, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) five, and and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acid as many as six. The two unsaturated fatty acid families, Omega-6 and Omega-3 are needed for vital functions at the cellular level, but cannot be produced by the body. That makes them essential - they must be obtained from the food "ready to use". For well functioning body, only the two basic short-chain forms, linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linoleic acid (ALA) are essential, since it can synthesize all needed longer-chain unsaturated forms from these two. However, enzymatic deficiencies preventing satisfactory conversion are rather common, making the longer-chain essential acids derivatives, in effect, also essential for affected individuals. YOUR BODY ┆ HEALTH RECIPE ┆ NUTRITION ┆ TOXINS ┆ SYMPTOMS |